DISQUIETED BEAUTY

Old Jail Art Center

Albany, Texas

2020

-

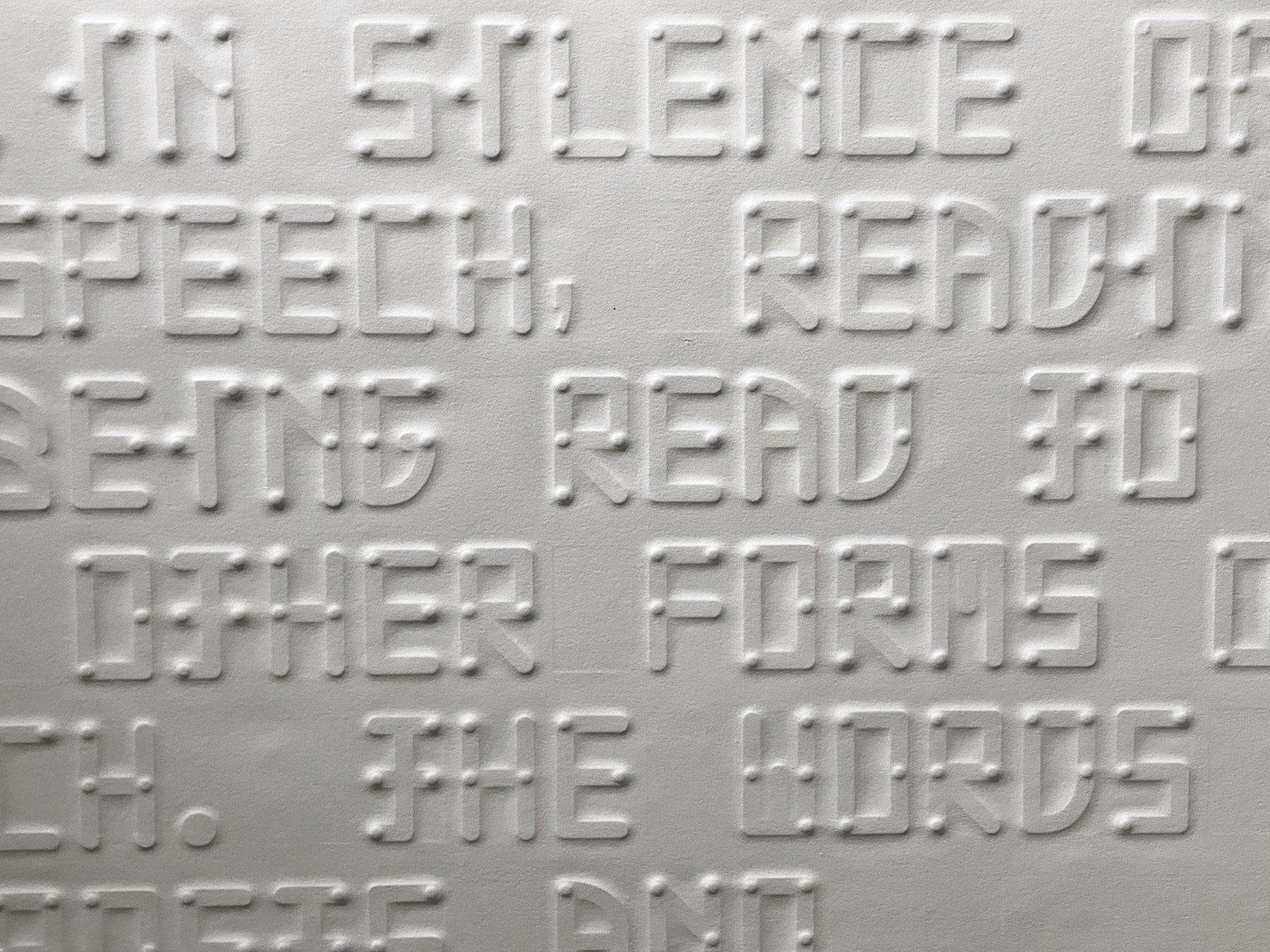

Disquieted Beauty explored human and animal cognition by examining different definitions of language and communication, namely, the neotropical orchid bee’s use of scent. The installation was constructed to engage the audience through visual, tactile and olfactory experiences meant to offer an insight into languages and modes of communication utilized by other species. The experiential and interactive exhibit pushed viewers to contemplate how communication amongst this planet’s diverse inhabitants requires careful attention to subtle differences, and an acceptance of unique perspectives. The gallery room’s walls were covered with embossed text and patterns derived from electron microscope images of orchid petals. Incorporating typefaces designed for the visually impaired, the tactile surfaces were impregnated with micro-encapsulated scent molecules identified from the orchid bee’s complex blend of volatiles. Viewers ran their fingers over the embossed words and picked up individual fragrances. When touching more text, the scents accumulated and became more complex, like words strung together in a sentence. In an adjoining gallery, fifty cast clay “bee smokers” referenced the shape and metallic greens, blues, reds and violets of the iridescent orchid bee. Patterns and colors were stenciled onto candy foil and wrapped around each bee smoker. These were arranged like organ pipes, alluding to the “perfumer’s organ,” an organization of shelves containing essential oils and aroma molecules used by perfumers.

-Jo Ann Fleischhauer 2020

-

PKQ1: To catch readers “up to speed” on you and your artwork, would you briefly describe your artistic practice? I know it involves research and integration of other disciplines.

JAF: I make installations. My interest lies at the interface of divergent disciplines: art, science, architecture and history. I often form collaborative partnerships with professionals in other fields to expand my art practice by delving into unfamiliar research, materials and processes. Disquieted Beauty followed a similar collaborative pattern. I worked with two orchid bee researchers, as well as the Institute for Art and Olfaction in Los Angeles to create an inter-media installation that explores the implications of a linguistic relationship between humans and non-humans.

My projects respond to the architecture, infrastructure and intended purpose of untraditional art spaces: an abandoned Victorian house, a highway overpass, a 19th century Italian oil mill, a historic clock tower, a grain silo, a decommissioned air traffic control tower, and currently the historic and repurposed jail cells at the Old Jail Art Center.

PKQ2: That answer directs me to thoughts and questions related to the art market as well as those I ask myself as an artist. The majority of the population see “art making” as a means to an end. The “end” being a tangible single product or item. Installations on the other hand contain objects that often rely on the context of the entire installation. Discrete items become products for consumption and installations more of contemplative endeavors. Your thoughts…and do you create discrete objects as well that can stand alone?

JAF: It’s an interesting and kind of humorous question because I’m always stressing about how I am going to fund my projects for the reason that they are experiential and I’m more concerned about the contemplative experience that I want the viewer to have when they are inside the installation. I do often make objects that are part of the installation. And because I frequently make “one of a kind” multiples or variations, there are a great number of objects that act as part of the greater whole or a layer of the broader idea. The quantity is an important aspect. But, because the objects are one of a kind, they can stand discretely as sculptures and people often comment that I should “sell” the objects separately. But for me, as a purist, I have a very difficult time thinking about them disconnected from the bigger idea.

Recently, I’ve been thinking a lot about the objects that I make which end up in boxes and storage. I’ve begun trying to think and construct my projects as having an ephemeral life, that is, that they don’t exist beyond the time of the exhibition. Of course, they live on as a photographic document, but the physicality is gone. But, then on the complete opposite end, I am a maker, and I love building things with my hands. It’s a hard balance thinking about waste, consumption and sustaining the future of the earth and the urge and need to fulfil an innate drive to make things. So, I go round and round of what I intend and wish to do and what my natural inclination is. The more waste we make as a culture and society, the more cognizant I am of my contribution to the equation. But it’s hard to get away from it completely.

In the end, the experience for the viewer in the space and the memory that lingers is more important to me than having an object to put on a shelf. The recollection, if strong, is as valuable to me than someone buying an object. But of course, the irony is there are budgets and costs to building such big projects. Therein lies the Catch 22.

What’s interesting about this project is that it is about searching for that balance between human and non-human beings within the broader question of the future of the planet. Obviously, this question is very prevalent and on most of our minds. How do we find that balance? Because always in the end humans are viewed as the dominant species. And, because of that power, we are responsible for the preservation or destruction of other species, both plant and animal. And I question how can we understand another species without functioning purely with an attitude of sympathy or stewardship. I don’t want us to just “take care of,” out of responsibility or guilt, because in my mind that ultimately doesn’t work. Most often, other species lose. I am trying to think about how we can communicate, with a genuinely balanced and equal relationship, and understand another species without taking an anthropocentric approach. It’s always stated that because we have the mastery of language both written and spoken that we are on the top of the food chain. But perhaps we don’t have the means of understanding how other species communicate, express, and relate.

PKQ3: That lack of understanding and communication is the root of much misunderstanding and mistrust among humans as well. So how do you see your work within your installation Disquieted Beauty addressing or illustrating bilateral communication?

JAF: I guess, of course, Disquieted Beauty could be interpreted as addressing a much broader and global question of human beings’ relationships, mistrust, and misunderstanding with other human beings. But once again in focusing the discussion on the human aspect, it takes the emphasis and urgency away from considering the human to non-human mistrust and misunderstanding. I’m trying to take the focus away from the human to human relationship.

During the Bosnian War, I did a project called Butterfly Effect. And I remember reading an article, which became the springboard for the installation, about the residents of Sarajevo. There was a severe shortage of firewood during the winter. Desperate, the people were going into the city parks and cutting down the trees to use for fuel. I was struck by a line that the author wrote… “and with the last trees go the last nests…” and I remember thinking how our destructive actions toward each other, our lack of understanding, communication and empathy, severely affects, without choice, the non-human inhabitants.

I realize I am part of that human equation and it’s a multi-layered, complex global question that does not have easy solutions. But on a personal and more manageable note, I want to be better at considering and understanding the world, human and non-human, and I work through those questions by making these environments.

PKQ4: Can you talk specifically about certain elements included in the installation and their relationship to the overall concept?

JAF: Disquieted Beauty will engage the audience through visual, tactile and olfactory experiences that offer an insight into languages and modes of communication utilized by other species, specifically the neo tropical orchid bee. Orchid bees use volatile molecules collected from orchids, plants and fungi to make a complex perfume for mating and communication. The bee’s method mimics how human perfumers create fragrances. The exhibition will push viewers to contemplate how communication amongst this planet’s diverse inhabitants requires careful attention to subtle differences, and an acceptance of unique perspectives. I wonder: could different isolated scents be considered characters in an alphabet? Could combinations and layers of fragrance be phrases, conversation, and therefore language?

One of the cell’s gallery walls will be covered with embossed text and microscopic images of orchid surfaces. Using fonts designed for the visually impaired, raised surfaces will be impregnated with microencapsulated scent molecules identified from the orchid bee’s complex blend of volatiles. The viewer will be invited to interact and touch the raised images. As they run their fingers over the embossed words, they will pick up individual fragrances. When touching more text, the scents will accumulate and become more complex, like words strung together in a sentence.

Many of the embossed white prints which will line the walls of the stairwell cell gallery are text based, excerpted from a variety of poems about scent and language and scientific papers about the orchid bee’s collecting and perfume making practices.

With regard to the cast bee smokers, ever since I became interested in bees, I have been fascinated by the bee smoker. On a purely sculptural level, I love the different shapes that the bee smoker has taken throughout its history and I love the musical references that it brings to mind; accordion bellows or the pumping sound coming out of an organ pipe. Ultimately, I saw the shape of the smoker as having a bee appearance and I wanted the orchid bee to be present in the space somehow. I started thinking about the smokers as bees. Then when I was casting them with this brown oil-based clay, I was suddenly thinking about Easter chocolate. And there was this realization of the beautiful sweetness of these bees and the perfume that they create. In addition, I wanted to reference the iridescent metallic colors and patterns of the different species, so I decided to wrap them in candy foil that I stenciled using abstracted patterns I made from photographs of different orchid bees.

PKQ5: Finally, does your scientific research make you optimistic or pessimistic about our relationship with nature?

JAF: Absolutely optimistic about the science, but maybe a little pessimistic about how it is used. I see science offering us a much better understanding of how nature works and our potential interactions with nature, but I am pessimistic that humans aren’t always taking advantage of that knowledge. I’ve discovered that there are many opportunities for us to benefit from a stronger relationship with our non-human world. Are we ready to act on those opportunities? I’m not always sure. I am hopeful and optimistic, however, that as time goes on, more of us will embrace and connect with the extraordinary around us.

PHOTOS BY PATRICK KELLY

PHOTOS BY DAKOTA GRUSAK